Nvidia Vs. Intel: The Semi Battle Of The Decade

Intel and Nvidia are on a collision course. Competition between both semiconductor giants will intensify. This could lead to headwinds for both.

Nvidia is on track to acquire Arm for $40 billion, getting access to the world’s most widely used architecture and top-class CPU design teams.

Arm is also trying to gain a foothold in (Intel's) data center, where Nvidia has also increased its efforts with Mellanox and GPUs for AI.

Intel, meanwhile, is developing a leading top-to-bottom GPU software and hardware stack, targeting all the same verticals as Nvidia.

The stakes are very high for both. Intel's biggest risk is its much higher revenue base, while Nvidia has a much steeper market valuation to lose.

Investment Thesis

For investors in semiconductor companies, there is a series of events unfolding that they may pay attention to. Intel (INTC) and Nvidia (NVDA), two of the largest companies of high-performance silicon, are on firm collision course. This means competition, which means changes in the landscape could and likely will occur, which means some analysis might be in order.

Nvidia is acquiring Arm and hence adding world-class CPU development to its assets - which is (also) Intel’s core competency. This seems quite a change in strategy, as Nvidia's philosophy to date has been to develop a (CUDA) GPU ecosystem where as many workloads as possible will be run on its GPUs - for example, adapting its CPUs with Tensor Cores instead of developing dedicated accelerators. Indeed, Nvidia's CEO called out the edge and AI as key drivers behind the acquisition, whose importance had already been highlighted years ago by prior Intel CEO Brian Krzanich. Intel, in fact, has a ~$4 billion IoT business led by a former Arm VP.

Moreover, Arm and Nvidia are also on track to expand their influence in the data center - which is (also) Intel’s core market and strategy. This is evidenced, for example, by the previous Mellanox acquisition and Arm’s Neoverse IP in, for example, Amazon’s (AMZN) Graviton chips. From Nvidia's comments, it seems it will further pursue and double down on this. Nvidia may become an Arm CPU vendor in the data center.

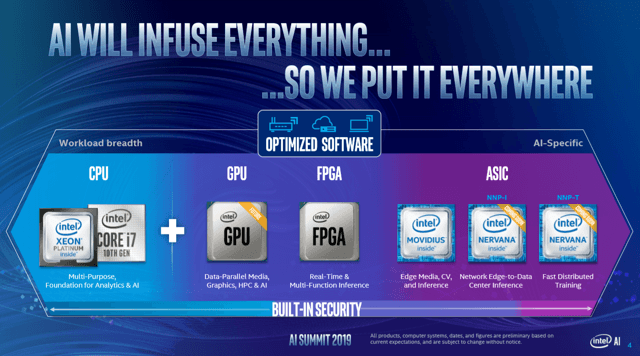

Intel, meanwhile, is finally close to launching its first GPU as part of its heterogeneous strategy: developing all kinds of silicon, not just only a CPU or only a GPU. Intel announced in late 2017 that it would develop a full-stack GPU software and hardware platform. These products will roll out over the next year and a bit. This will mark the start of Intel’s inroads in what remains Nvidia’s core business, of course. As Intel says, its customers are asking Intel to enter this market.

Thirdly, although Mobileye’s strategy is much broader, Intel and Nvidia are also both seen as leaders in self-driving vehicle silicon.

The outcome of this collision course is hard to predict. In the past, Nvidia and Intel were hardly competitors, but going forward, they will compete in discrete GPUs, in (data center) CPUs, in IoT, in AI accelerators, in networking hardware and in automotive.

Nevertheless, while this clearly is a drastic change that is occurring, Nvidia bulls will be extremely reluctant to believe that the company will get a worthy, well-funded GPU competitor - which by revenue actually makes Nvidia look like the small player. Intel bulls, meanwhile, will react to Arm’s efforts in the data center - Arm tried this before already and failed. AI may actually be the area where both companies are most evenly matched (in terms of revenue, portfolio).

The results, hence, will be determined by product and sales execution/competition in the long run. Such competition could go either way, of course: Nvidia could lose (much) AI and GPU market share, while the same holds for Intel in the data center.

Both Intel and Nvidia have high margins, especially in the data center, but that also creates opportunities for both to be (more than) competitive on pricing besides just competing on performance.

In terms of valuation, despite being the much smaller company in revenue and profits, Nvidia this year raced past Intel, while the latter dropped on concerns about its future competitiveness. Nevertheless, it could be said that Nvidia investors pay 50% more for over 80% less revenue (and 75% less in the data center even after the Mellanox acquisition), which does not sound like a good deal - although Nvidia is now putting those expensive shares to work to fund its acquisition.

What happened previously

Much of the increased competition already started unfolding several years ago. Some key facts:

- In response to the growing GPU adoption for AI in the data center in 2016, Intel acquired Nervana, and Movidius for edge AI.

- In response to the self-driving vehicle hype, which Nvidia also participated in, Intel first partnered with Mobileye in 2016 and acquired it in 2017.

- Intel announced in 2017 it would develop a full-stack GPU portfolio.

- Intel announced in 2018 it was developing a full-stack open software ecosystem for heterogeneous computing (with beta released in 2019 and 1.0 launch in 2020), including a CUDA conversion tool.

- Nvidia outbid Intel to acquire Mellanox in 2019.

- Subsequently, Intel ("instead") acquired start-up Barefoot Networks.

- In late 2019, Intel acquired Habana, and shortly thereafter, canceled the Nervana roadmap. Intel also confirmed its GPUs would also be targeting AI with its own version of Tensor Cores.

What will happen now

The Arm acquisition will further intensify competition:

- Nvidia will proliferate its GPU IP throughout the Arm ecosystem, likely as a 1:1 replacement of Arm's current Mali GPU IP.

- While continuing the Arm licensing business and data center roadmap, Nvidia is likely to become a prime vendor of Arm CPUs for the data center as well as IoT, as a direct competitor of Intel's x86 chips.

- Over the next year, Intel's first GPUs will be released across the various markets GPUs are used in.

Keep in mind, though, that the Arm acquisition, if it actually goes through, could take another 18 months to actually complete in the first place. So near term, not much will change on that side yet. Also, given Arm's licensing model, the second bullet point was already possible before.

Thoughts on Arm acquisition

Commenting on the acquisition itself. My primary criticism is that it is not obvious at all how this will create synergies, as their business models do not really seem to mesh well together: Arm licenses isolated IP, while Nvidia develops full-stack solutions.

If, on one hand, Nvidia wants to broadly license its CUDA IP, to achieve GPU world domination so to speak (which indeed seems to be the case), then it has to give up its high ASPs in favor of much more modest licensing fees. So the value this generates and the ROI isn't clear or obvious. Moreover, in an age where customers increasingly demand full solutions to solve their needs, instead of (demanding) isolated IP, this seems like a step down.

On the other hand, the relatively small Arm licensing fees actually already allowed for the creation of such Arm + Nvidia solutions... without having to acquire the whole business.

This new strategy itself also isn't obvious given that 95% or so of its GPUs currently attach to x86 CPUs.

For Nvidia's GPU business, it doesn't matter a ton which CPU its GPUs attach to (Arm or x86). Perhaps Nvidia has bigger ambitions, wanting to play a bigger role in its customers' success. This would be the same strategy as Intel, and indeed, evidence of the collision course I mentioned: Intel lacked accelerators, so it acquired Movidius, Nervana, Altera, etc., while Nvidia lacked CPUs, and thus felt compelled to acquire Arm.

Another motivation for the acquisition is to increase Nvidia's presence at the edge and IoT, about which both Nvidia and Intel are very bullish. Nevertheless, acquiring Arm outright doesn't seem like the best option for that: both due to criticism in the tweet above, as well as my comment above about entering the licensing business being a "step down". Especially in IoT: Intel's strategy is to provide end-to-end solutions for many verticals.

So, in any case, if Nvidia's goal is now to make 95% of its GPUs attach to Arm CPUs instead, then it has to go through the poor man's licensing model. Nvidia can't achieve both 95% Arm adoption while also maintaining an open Arm ecosystem and its desktop and server GPU ASPs. In that sense, acquiring Arm just for the sake of replacing its Mali GPUs with CUDA ones likely won't generate a lot of value.

If anything, it would be ironic if someone were to license Nvidia GPUs and enter Nvidia's PC and data center markets by beating Nvidia on pricing.

How about CPUs in the data center? Perhaps Nvidia is looking to foster a complete, worthy alternative ecosystem to x86. That would be ambitious, of course, and faces about the same challenges as Intel building a GPU business or AMD its server business: starting from zero market share. Or even more so given the completely different ecosystem: last decade, Intel tried entering smartphones with x86, at a time when it still had a vast process lead (those low-power FinFETs), and failed. It remains to be seen if Nvidia could be any more successful in creating a meaningful data center Arm ecosystem.

TAM

As a small aside to address one highly upvoted comment:

I’m having a hard time imagining a single other company in the world with a larger TAM than what Nvidia could be looking at in the next 5-10 years. Nvidia confirms $40B deal for Arm Holdings

The TAM of GPUs, as Nvidia's revenue shows, is decent, but simply is no match for Intel's depth of IP... I continue to be amazed by investors praising Nvidia while simultaneously brushing aside Intel's comprehensive portfolio of products and solutions (targeting the same data center market also).

Intel has a $300 billion TAM and $200 billion long-term Mobileye TAM. On the other hand, Arm seems to add perhaps a few billion dollars in IP licensing TAM?

So, in essence, while Nvidia boasted about adding over 10 million developers to its ecosystem, and may be strategic in several other ways, I fail to see the tangible value that Nvidia could gain from the Arm acquisition, as explained above.

Intel GPUs

As I have detailed in several articles before, Intel’s progress in GPUs instead is much more straightforward. For Intel, developing discrete GPUs represents a logical step, as it was already designing ever-more-capable GPU IP for its integrated graphics. By developing discrete GPUs, it can now directly monetize this development effort (which will result in a third competitor besides Nvidia and AMD). So, while it represents a new market, Intel's history as an integrated graphics provider may provide credibility to potential customers for adoption. And as the company will say, its customers are also asking it to do exactly that: the sooner the better.

In my analysis of Intel’s efforts, I have concluded that the company is indeed on track to have highly compelling and competitive solutions in the next year or so, both on the hardware and software side. After all, Intel is a well-funded company that suddenly makes Nvidia look like the small player in scale.

As far as a software is concerned, Intel is on a multi-year journey to develop its oneAPI initiative as a more than capable competitor to Nvidia CUDA, as it is much broader in scope than just GPUs, and encompasses both CPUs and all of the heterogeneous compute architectures that Intel is developing - allowing developers to manage just one code base instead of many. As an open initiative, there is also support for CUDA, whether native or via an Intel-provided conversion tool.

On the hardware side, Intel is innovating its way into the market via multi-tiled GPUs by leveraging its industry-leading packaging capabilities. For example, the 4-tiled version of Intel’s 2021 Arctic Sound will have at least twice the single precision throughput (performance) as Nvidia's latest Ampere A100. While AI throughput has not been disclosed yet, some estimates based on one tensor core per execution unit indicate that it may also have a tangible performance advantage on that front.

While Intel will obviously start from zero in discrete GPUs (not unlike Arm in the data center though), leading products are the first requirement to gain momentum, and Intel looks on track to deliver exactly that.

Moreover, given Nvidia's gross margins, it should not be particularly hard to set competitive pricing; I am sure Nvidia bulls can't imagine anyone overtaking the company, but pricing and access to the same foundries (in addition to its own manufacturing and packaging) are two levers that can make this possible. In the end, those GPUs serve to allow gamers to play games, and reviews will make very clear how Intel's offerings stack up against similarly priced competitive offerings.

Summed up, I see Intel announcing in 2017 developing its own discrete GPUs and hiring ("acquiring") Raja Koduri as very similar to Nvidia now acquiring Arm: both moves shook the industry apart, but took or will take quite some time to materialize.

Larrabee and Arm data center failures

Since investors may be interested not just in knowing what's happening in the market, but what the outcome will be, I had a section discussing this. Upon consideration, the argument wasn't as strong, but the gist of the insight was that both Arm entering the data center and Intel developing GPUs isn't exactly new... and both parties actually failed in their previous efforts. (For example, Qualcomm's (QCOM) high-key Centriq effort and Intel's Larrabee many-core CPU.)

For various reasons, though, "this time may be different" may apply to both sides: Intel's competitiveness has declined given its 10nm delays, for example, while Intel now developing "real" discrete GPUs.

The Cloud and Data Center

While I claimed that Intel and Nvidia are on a competitive collision course, one could also argue that they are "imitating" their strategies to some degree. The next few sections will provide some illustrations of this.

While Intel has already for years been pounding on the table exclaiming that it is becoming a data-centric company, now Nvidia too has taken a page out of this playbook to become a data center-first company, as described, for example, in this article: "Nvidia: Why It's Still Early Innings".

This is one of the key Nvidia bull arguments to likely have propelled the stock. Nevertheless, Intel is already much further along this trajectory, but its valuation has not seen such an increase. Nvidia still has on the order of 7x less overall revenue and 4x less data center revenue even after the Mellanox acquisition, so valuations seem elevated far beyond fundamentals. I suppose Intel's much larger revenue base makes Intel appear a worse investment, as growth is always measured in percentage growth, not in absolute dollar growth.

AI

Both Intel and Nvidia also compete at the edge-IoT and in AI. Nvidia actually did not so much call out the data center as it was expressing AI as the driver behind the acquisition. This is also similar to Intel. I already discussed this in quite some detail previously: "Intel To Lead The AI Revolution Over The Next Decade".

IoT and Strategy

Both Intel and Nvidia are also developing AI accelerators for the IoT-edge, and Intel calls Nvidia its biggest competitor there. Of note, Intel's IoT group is led by a former Arm VP, who said he joined Intel for exactly the value chain argument above: to create full solutions for verticals, which shows the limitations of the licensing model (he faced while at Arm). To be sure, Intel's ASP in IoT is >$100, so it not competing with low-cost, low-performance Arm chips.

One comment caught my attention. Nvidia's CEO called out the Internet of Things as the driving force behind all this, which he contrasted to today's Internet of People.

“AI is the most powerful technology force of our time and has launched a new wave of computing,” said Jensen Huang, founder and CEO of NVIDIA. “In the years ahead, trillions of computers running AI will create a new internet-of-things that is thousands of times larger than today’s internet-of-people. Our combination will create a company fabulously positioned for the age of AI.

Intel's prior CEO, Brian Krzanich, many years ago already called out exactly the same trend: that the cloud of the next decade would be powered mostly by things, not by people, and would therefor become much, much larger than it was back then.

So, it seemed like I was suddenly reading an Intel press release. This shows that in strategy, and therefore, execution to that strategy, Intel actually may be vastly ahead of Nvidia. In that sense (for example, by recognizing it needs a credible solution for edge AI and that this requires CPUs), Nvidia seems to be imitating Intel more than Intel is imitating Nvidia.

In any case, both are definitely AI-first companies. Their competitive collision course or similar/convergent strategies overall seem to validate each other. Both companies are pursuing for a large part the same opportunities. For investors, this likely means both Nvidia and Intel present very similar investment opportunities, although with key differences.

Heterogeneous future

Much of the above can also be looked at from the trend of heterogenous compute.

About that point specifically, a small (more technical) comment about how those different compute solutions are connected. While most companies have proprietary solutions, the industry in the last few years has seen the need for open interconnect standards to enable what is called coherent attachment (which more or less gives the capability of accessing a unified memory pool to all connected silicon).

Multiple such open standards have been developed, but the one that has garnered the most momentum is Intel's CXL: even Arm last year largely abandoned its own CCIX in favor of CXL. As these interconnects are mainly relevant in the data center, this may be illustrative of who still really has the upper hand as leader in the data center (despite what the market valuations imply).

So in that sense, while Nvidia is clearly on a path to become more independent from Intel, it is slightly ironic that even into the future, the "glue" between Nvidia and Arm could very well be Intel's CXL.

Lastly, Intel has often talked about its "six pillars of innovation" strategy (since 2018), from process technology to software. I would argue that Intel is the only company that actually has all of those six pillars. To be specific, Nvidia still lacks memory and storage. Perhaps Nvidia could (or will have to) acquire Micron (MU), Intel's former IMFT JV partner, next?

Summary

The key points:

- Synergies? Few to none: Arm designs IP, Nvidia sells solutions.

- Nvidia could (and did) already create Arm-based solutions.

- The IP licensing business is moving down in the value chain, not up.

- IoT: Given that Nvidia's CEO's comments echo those of Intel's Brian Krzanich many years ago (virtuous cycle of edge and cloud), it seems Nvidia is somewhat imitating Intel's data-centric efforts. Both companies share a similar strategy, which leads to a competitive collision course, and both also validate their strategies. But contrary to Nvidia's statements, I deem Intel will remain the "premier computing company".

- Intel developing a full-stack GPU portfolio, led by industry veteran Raja Koduri (former AMD, Apple (AAPL) executive).

- Nvidia's valuation seems mostly based on price-demand for the stock, and does not seem a realistic reflection of the company's value based on revenue and/or earnings. It pays over 50% more for over 80% less.

Takeaway

At present, the distinction is quite clear: Nvidia is the firm leader in discrete GPUs in all verticals, while Intel holds the same position in the data center and CPUs.

Intel's ~$4 billion IoT business also illustrates one of the main criticisms about the Arm acquisition: the lack of clear synergies it will provide (given the different business models), and arguably, lack of meaningful value, as licensing is much lower in the value chain; with Intel instead delivering full market-ready solutions. (In September, Intel announced Atom and Tiger Lake CPUs with specific features and software/tools for IoT at its Industrial Summit.)

Nevertheless, the trend of the last few years is that Nvidia and Intel are on a competitive collision course, even as far as imitating each other's strategies goes. With the Arm acquisition, this may lead to Nvidia becoming a CPU vendor in the data center, while Intel is on the verge of starting its full-stack GPU roll-out.

Contrary to just a few years ago, this inflection makes them competitors in more markets than ever: CPUs, GPUs, networking (interconnects), IoT-edge, AI accelerators, autonomous vehicles...

At present, there seem few definite indicators of how both companies will stack up in the long run: Arm adoption in the data center remains wait-and-see, and cloud companies already have a serious competitor to Intel anyway with AMD. For Intel, it is anyone's guess how much and how fast it could gain market share in GPUs, even though it likely will have more-than-competitive offerings. So, at least near to mid-term, Intel will still be king of the data center and will remain so for the foreseeable future - as will Nvidia in GPUs, admittedly.

Intel and Nvidia are the definite leaders in their core domains, and will not give up those positions for free, even if they are now heavily attacking each other in exactly their respective core domains. The vigor with which both are pursuing those efforts does seem to imply that there could be quite some changes in market share and competitiveness over time.

There is one common point that makes them competitors (but also similar) more than any other point: their strategywith their heavy focus on AI (and IoT) and their bullish stance on the need for (compute) performance: data-centric, software-enabled.

The only thing Intel seem to have "against" it is its much larger revenue base, which makes growing at large percentages unfeasible, even if many businesses within Intel as a conglomerate are highly compelling. Nevertheless, other large companies such as Apple show that slower-growing companies can also trade a high valuations.

If I had to make any concrete investment thesis, I would just point out that objectively, Nvidia investors pay 50% more for over 80% less revenue. This suggests that Nvidia's valuation is substantially based on hype, even though, if anything, Intel may overall slightly have the edge. Nevertheless, Nvidia investors will likely not complain that these expensive shares are now substantially funding the Arm acquisition. Still, I would suggest that if investors like Nvidia, given all the similarities (such as AI, data center) but also key differences (such as revenue, portfolio, IDM model), they may like Intel even more.

The stakes are clearly high for both: Intel has much it could possibly lose given its vastly larger revenue base; while Nvidia has a much, much steeper stock market valuation to lose.

Disclosure: I am/we are long INTC. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Additional disclosure: For those going to the comment section to comment on my disclosure: my Intel position is a single digit fraction of my portfolio, initiated after the recent historic 7nm stock sell-off (and which actually happened to be on the same day that CEO Bob Swan also doubled down on his Intel position as a vouch of confidence in his company).