Broward School Violence: Cruz's Massacre Is Far From the Whole Story

Broward County, Fla., school officials portray as a great success their Obama administration-inspired program offering counseling to students who break the law, instead of having them arrested or expelled. They insist that it played no role in February’s school massacre by Nikolas Cruz. They also claim that in fact juvenile recidivism rates are down and school safety is up, thanks to the program.

The evidence tells a far different story.

Broward County juvenile justice division records, federal studies of Broward school district safety and the district's own internal reporting show that years of “intensive" counseling didn’t just fail to reform repeat offender Cruz, who allegedly went on to shoot and kill 17 people at his high school. Records show such policies have failed to curtail other campus violence and its effects now on the rise in district schools — including fighting, weapons use, bullying and related suicides.

Meanwhile, murders, armed robberies and other violent felonies committed by children outside of schools have hit record levels, and some see a connection with what’s happening on school grounds. Since the relaxing of discipline, Broward youths have not only brazenly punched out their teachers, but terrorized Broward neighborhoods with drive-by shootings, gang rapes, home invasions and carjackings.

Broward County now has the highest percentage of “the most serious, violent [and] chronic”juvenile offenders in Florida, according to the county’s chief juvenile probation officer.

Before the massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, the program’s most supportive community partner – the county sheriff’s office – privately worried that school-based deputies were overlooking increasingly dangerous threats. It warned that violent felons on probation were getting “several chances to reoffend” under the school program and those who put their victims in the hospital after attacking them on school grounds escaped arrest through the program.

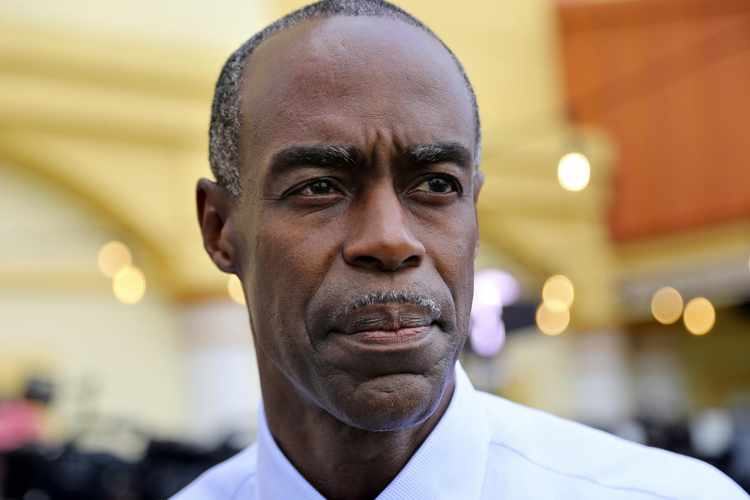

Broward Schools Chief Public Information Officer Tracy Clark.

Records also show that Cruz was not the only active-shooter threat in the Broward school system. Since 2015, at least three other pupils have brought loaded firearms into schools and threatened to go on shooting sprees.

Nevertheless, Broward schools Chief Public Information Officer Tracy Clark denied the district’s reforms have weakened safety. "In fact,” she said, “our district’s overall disciplinary incidents have dropped since we adopted the new policy and wraparound supports to students with behavior issues."

District officials, however, declined to provide evidence when presented with contrary reporting by RealClearInvestigations.

The administration has kept a lid on such bad news by suppressing school safety data, including canceling annual surveys of student behavior.

“Their program is a lie, and it doesn’t work,” said Lowell Levine, a father with grown children whose Stop Bullying Now Foundation in Lake Worth, Fla., has received several dozen complaints during the past few years from parents whose children were repeatedly beaten and bullied by fellow Broward students, who suffered few or no consequences.

As a result, some parents have sued the school district for failing to protect their children from violent attacks. At least one survivor of the Feb. 14 shooting is filing a lawsuit citing the district’s lax discipline policies.

Levine said he alerted Broward Schools Superintendent Robert Runcie’s office about the flood of complaints regarding school violence in 2015, two years after its leniency program, called PROMISE, was put into effect. (PROMISE stands for Preventing Recidivism through Opportunities, Mentoring, Interventions, Supports & Education.)

“But he refused to meet with me,” said Levine, who has been consulting with survivors of the Parkland shooting. “I was told they had it under control and that they didn’t need any outside advice.”

Runcie’s office did not respond to requests for comment regarding Levine’s claims.

Runcie and the Broward school board have agreed to hold a community forum Wednesday to address growing concerns from parents and students about the role the PROMISE program played in the shooting and overall school safety.

“The PROMISE program has failed us, and discipline hasn’t been allocated the way it should have been,” parent Donald Eckler told the board during a public meeting this month. “We’ve shut off communication between the school board and the police agencies that impact these students.”

That new discipline policy took effect in 2013. It was at the vanguard of the Obama administration’s efforts to address the “school to prison” pipeline. Beginning in 2009, it opened hundreds of investigations or sued to force districts to adopt lenient discipline guidelines. This push was formalized in a 2014 “Dear Colleague” letter to the nation’s public school superintendents and board members that not only discourages student arrests, but holds districts liable for the actions of school resource officers.

After meeting with Obama officials in the White House, Runcie persuaded the Broward County Sheriff’s Office and Fort Lauderdale Police Department to agree to stop arresting students who committed misdemeanor crimes the district deemed “nonviolent” – including assault, theft, vandalism, drugs and public fighting. This included multiple offenders such as Cruz. Law enforcement agreed for the most part to let school officials handle such delinquents through two counseling programs: PROMISE and the Behavior Intervention Program.

Runcie argued that diverting minor offenders from jail to “restorative justice” counseling and other positive behavioral interventions would help close the academic "achievement gap” by disrupting the flow of black students into the so-called “schoolhouse to jailhouse pipeline.” Though African-Americans made up about 40 percent of the Broward student body, they accounted for more than 70 percent of juvenile arrests in the county.

In a related program, Broward County Sheriff Scott Israel also agreed to back off arrests of students who commit such crimes outside of schools, offering them civil citations and the same “restorative justice" counseling instead of incarceration, even for repeat offenders. Restorative justice is a controversial alternative punishment in which delinquents gather in “healing circles” with counselors – and sometimes even the victims of their crime – and discuss their feelings and the "root causes" of their anger and actions.

Broward Superintendent Robert Runcie.

Within two years of adopting the discipline reforms, Broward's juvenile recidivism rate surged higher than the Florida state average.

The negative trends continued through last year, the most recent juvenile crime data show.

Prosecutors and probation officers complain that while overall juvenile arrests are down, serious violent crimes involving school-aged Broward youths – including armed robbery, kidnapping and even murder – have spiked, even as such violent crimes across the state have dropped.

Juvenile arrests for murder and manslaughter increased 150 percent between 2013 and 2016. They increased by another 50 percent in 2017. County juveniles were responsible for a total of 16 murders or manslaughters in the past two years alone, according to the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice.

Last year, the number of Broward juveniles collared for armed robbery totaled 92, up 46 percent from 2013, department data show. Arrests for auto thefts jumped 170 percent between 2013 and 2017 – from 105 to 284. Juveniles charged with kidnapping, moreover, surged 157 percent in 2016 and another 43 percent last year.

Broward Juvenile Delinquency Division Judge Elijah Williams, who has given full-throated support to the PROMISE program, acknowledged “a growing problem in the community where gangs of children are stealing cars,” according to minutes of a 2017 Juvenile Justice Circuit Advisory Board meeting.

Max Eden, an education policy expert and senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, said the no-arrest policies for students of all races has demonstrably “emboldened” criminality among Broward youth, including Cruz, whose infractions became steadily more violent. Recent studiesshow juveniles often commit more serious crimes when petty crimes are not punished.

Thousands of arrested Broward students have had their records deleted in the system as part of a program to end “disproportionate minority contact” with law enforcement, blindfolding both street cops and school resource officers to the criminal history of potential juvenile threats.

In addition, “the actual police reports are being destroyed,” stated Broward juvenile prosecutor Maria Schneider at a recent Juvenile Justice Circuit Advisory Board meeting. She added that heroffice has added a full-time attorney to handle expunctions.

Meanwhile, “scared straight” field trips to the juvenile jail are now a thing of the past. And juvenile probation officers are discouraged from visiting schools.

After Broward schools began emphasizing rehabilitation over incarceration, fights broke out virtually every day in classrooms, hallways, cafeterias and campuses across the district. Last year, more than 3,000 fights erupted in the district’s 300-plus schools, including the altercations involving Cruz. No brawlers were arrested, even after their third fight, and even if they sent other children to the hospital.

Federal data show almost half of Broward middle school students have been involved in fights, with many suffering injuries requiring medical treatment. The lion’s share of the campus violence is taking place at middle schools and high schools in Miramar, Coconut Creek, Fort Lauderdale and Plantation.

New Renaissance Middle School in Miramar.

At South Plantation High School, for instance, all-out brawls involving dozens of students have been reported regularly in hallways and the cafeteria.

One frustrated parent, Santiago Ortega, said his 14-year-old son was so afraid of being jumped by upperclassmen that he routinely hid in a bathroom stall during school. Ortega said he both called and emailed the superintendent's office – and even tried to personally reach out to Runcie – to complain. But, he said, nothing was done. Frustrated, he recently transferred his son to a different school.

“They need more security,” the father complained. “And they need to actually address the issue.”

Because the students involved in the fights are considered “mutual combatants,” administrators tell parents they cannot be referred to police under the new discipline code.

Parents are reportedly so worried their kids will be attacked unawares that they have advisedthem to remove their cellphone music earbuds while walking the hallways to better hear assailants approaching from behind.

In a December 2016 fight caught on video at Plantation High School, several girls beat and dragged another girl to the ground and took turns kicking her. Campus police did not break up the fight and the girls who jumped her were not arrested. The attacked girl’s mother said the school failed to stop bullying before it escalated into violence, and then swept the incident under the rug. Three other fights reportedly broke out the same day at the school.

A Plantation teacher recently told a local TV station that school fighting, which she says has grown more fierce and frequent, often is not reported to police or administrators “because of politics.”

Earlier in the year, another girl was jumped by several girls as she walked down a flight of stairs at New Renaissance Middle School. Jayla Cofer ended up in the emergency room with deep lacerations and bruises to her face. Though a school resource officer broke up the fight, no arrests were made. Instead, the girls were sent to the PROMISE program for a few days of counseling sessions, which are held at Pine Ridge Education Center in Fort Lauderdale.

Jayla Cofer’s mother, Santrail Cofer, reported the incident to Miramar police and filed a lawsuit against the school district for failing to send the assailants to jail or remove them from school.

Rosalind Osgood, a Broward County school board member whose district includes Plantation High, acknowledged at the time the district has a fighting and overall violence problem. But she argued arrests and other harsh punishments are not the answer because they do not address underlying emotional issues that lead to aggression.

“I don’t want schools to be a place where we’ve got gobs and gobs of officers walking around,” said Osgood, who chaired the board in 2013 and was one of the original signers of the no-arrest mandate. “I’m trying to keep kids out of jail, so I don’t want to create a jail environment.”

In October 2016, a potential school shooting was thwarted at Coral Springs High School thanks to a student who alerted a school resource officer after spotting a gun in the waistband of a former student who had entered the cafeteria. The 17-year-old former student, Ryan Trollinger, allegedly planned to give the loaded 9 mm handgun to an enrolled friend who authorities said planned to use the weapon for a “massive school shooting.”

Dexter M. Williams, Miramar police chief.

The other student, a juvenile who was not identified, reportedly wrotein a journal: “I want to be the worst school shooter in America. Worst [sic] than Columbine, Virginia Tech, and Saney [sic] Hook.” Trollinger got 15 days detention, counseling and community service, while the would-be shooter was sent for psychiatric evaluation and was not charged with a crime.

The scare at Coral Springs High followed the discovery a year earlier of a .357 Smith & Wesson handgun, ammunition, mask and knife in the backpack of a Sunrise Middle School boy in that school’s cafeteria.

Around the same time, another Sunrise Middle School boy punched his 62-year-old science teacher in the face – bloodying her nose, injuring her eye and causing a concussion – because she told him he couldn’t bounce his basketball in the classroom.

It was the second physical attack on the teacher, Ruthanne Stadnik, in two weeks at the Fort Lauderdale school.

“They feel there are no consequences,” she said.

“Unfortunately, it’s not an unusual event,” Broward juvenile prosecutor Schneider said at the time, adding that district children have also struck "school board employees.”

Although the local prosecutor originally signed on to the PROMISE agreement, she cautioned that backing off the arrest and prosecution of too many delinquent students could end up “making the schools a more dangerous place.” Just a few months after the agreement was finalized in November 2013, Schneider warned school officials who were worried about criminal records “stigmatizing" minority youth: “There has to be accountability for bad behavior.”

Local police have become frustrated with crime spilling over from schools, and have pushed back against the PROMISE program, which, some officers suspect, “students are utilizing as a pass-through to run drugs through the schools,” according to minutes of a recent meeting of Broward's Juvenile Justice Circuit Advisory Board.

Critics say school officials knew the student safety picture was darkening and tried to gloss over it.

In 2014, the year after discipline reforms took effect and school safety data started trending badly, Broward stopped asking students key safety questions in an annual survey, including whether they “feel safe” in the classroom, restroom or cafeteria, or whether they have “seen students with weapons at school." The next year, the district stopped publishing its yearly school-climate surveys entirely.

"In 2014, they removed the six questions directly asking students whether they felt safe,” Eden said. "After 2015, they discontinued the annual survey they had been conducting for 21 years.”

The district did not respond to requests seeking explanation for the discontinued school safety surveys.

The federal government, however, conducts its own annual survey of the climate at major districts across the country. The data for Broward show a deterioration in safety indicators after the discipline reforms were adopted.

Between 2013 and 2015 (the latest data available), weapons possession, fighting, bullying and attempted suicide all rose for Broward high schools, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control. More than 17 percent of students avoided going to school at least once because they felt unsafe. There were more than 70,000 students enrolled in Broward high schools in 2015.

Meanwhile, the CDC’s survey of Broward middle schools showed 33.5 percent of the 1,503 students surveyed in 2015 had been bullied on school property. Almost half – 47.4 percent – had gotten into fights, with more than 4 percent resulting in injuries treated by a doctor. Nearly 20 percent carried a gun, knife or club to school, up from almost 18 percent in 2013, while one in five also seriously thought about killing themselves.

The most recent state data, moreover, show that the Broward school system now has the highest rate of weapons-related incidents in South Florida.

Dr. Rosalind Osgood, school board member.

In 2017 alone, there were at least 10 reported cases of students taking their own lives, along with “a tremendous increase in the calls on suicides," records show, prompting the district to implement "special response teams" to prevent more suicides. Even elementary school children are attempting suicide.

“Bullying has become deadly,” Levine said. On his recommendation, several families have pulled their victimized children out of the Broward school system.

He warned that Broward's lenient discipline policies, which fail to mete out harsh consequences to bullies, have fostered an environment that could cause a victim to snap in other ways. “Cruz was badly bullied in middle school and high school,” Levine pointed out.

In addition to PROMISE, the Broward school district has created another counseling program for students with severe behavior problems and violent tendencies, and has found limited success with it as well.

RealClearInvestigations has learned that Cruz was assigned to the more “intensive” counseling – administered through the Behavior Intervention Program – after several violent incidents and before the Valentine’s Day shooting.

In lieu of arrest for a string of serious infractions, Cruz was diverted to the Cross Creek School, which is part of the Behavior Intervention Program. The counseling at Cross Creek lasts months (versus days at PROMISE’s Pine Ridge facility), but critics say it is part of the same misguided social program to divert law-breaking students from jail.

Despite several months of counseling, Cruz’s behavior did not change. His Cross Creek counselors noted he continued to exhibit several disturbing behavior patterns, including an obsession with guns and violence.

Yet in January 2016, he was transferred back to Stoneman Douglas High. After he brought bullets to school in a backpack, school authorities barred him from wearing a backpack but did not refer him to law enforcement, even though it was a Class B weapons violation and an arrestable offense, according to the school’s disciplinary code. Records show he also was involved in multiple incidents of fighting and a serious assault there that triggered a “threat assessment.” At the same time, he posted threatening messages against the school on social media.

The district declined to provide information detailing the counseling and other interventions that Cruz received while in the district-wide Behavior Intervention Program (formerly Behavior Change Program/Discipline Centers).

"Our office is unable to provide any information on your inquiry, as this falls under the rules protecting student information and records,” Broward spokeswoman Cathleen Brennan said.

The renamed Behavior Intervention Program was expanded in 2013, the same year Runcie signed the “collaborative agreement” with the county sheriff, police chiefs, prosecutors and juvenile court judges to keep lawbreaking students in school.

Broward Deputy Sheriff Jeff Bell, who also serves as president of the Broward Sheriff’s Office Deputies Association, said that deputies working as school resource officers (SROs) in the Broward County school system were trained to counsel and mentor disruptive and lawbreaking students rather than take them into custody.

“They were basically paying us not to make arrests,” he said.

Robert Martinez, a Broward deputy who worked as a school resource officer for nearly two decades, agreed. He said the school district wanted to keep arrest numbers down at all costs, and actively discouraged school resource officers from taking lawbreaking students into custody. He said removing a dangerous teen like Cruz from a school can take up to two years due to all the red tape that was added to the process by Runcie's new discipline policies and programs.

Martinez, who retired last year after 18 years stationed at various Broward schools, added that the number of sheriff's deputies assigned to area schools has in recent years been cut in half, to about 30, as they've come under increasing political pressure to look the other way when students break the law.

Maria M. Schneider, assistant state attorney in charge of the Juvenile Division for the 17th Judicial Circuit of Florida.

“I started in 1997, and we had approximately 60 SROs,” he said, adding that the shortage has hurt school safety.

Records show their bosses were also uneasy about the new policy.

Less than two months after the signing of the no-arrest agreement, the executive staff of the Broward Sheriff’s Office expressed concerns that deputies were unable to ascertain whether gang members, repeat offenders or violent kids on probation were committing crimes inside schools due to the constraints of the PROMISE program, minutes of a 2014 meeting with school officials and other members of the Juvenile Justice Circuit Advisory Board reveal.

“According to the [new discipline] matrix, that kid may get several chances to reoffend,” saidDavid Scharf, executive director of community programs for Broward Sheriff’s Office.

Friction also came from the state attorney’s office. Around the same time, juvenile prosecutor Schneider complained that students committing aggravated battery – a violent felony – were being classified as "non-violent" misdemeanor offenders and referred to PROMISE counseling instead of jail.

“If this is the definition that is now being utilized, there is a problem,” she said, "because that is not the definition that the state attorney, [police] chiefs, or the sheriff signed onto.”

Added Schneider: “There are incidents that qualify for PROMISE where a child needs to go to the hospital, and that should not be happening."

Last year, then-Fort Lauderdale Police Chief Frank Adderley informed school officials in another meeting of the juvenile justice board that his “officers expressed concerns their discretion [was] being taken away.” Miramar Police Chief Dexter Williams, moreover, relayed that his “officers do not like not having the discretion” to arrest lawbreaking students.

In addition, district records show aides used juvenile arrest data to target the strictest schools for investigation, along with the school resource officers assigned to the schools who made the arrests, and then made changes in interagency contracts that dramatically diminished the role and overall profile of law enforcement on the campuses.

In 2014, Broward joined with the Department of Juvenile Justice to tally the number of students classified as “school-related arrested.” Then it developed a data-matching process to “drill down to the specific school where the arrest occurred to create systemic change,” according to a Broward County schools document.

The school district "transformed not only district policies and practices, but the policies and practices of local law enforcement and the juvenile justice system,” it boasted in another document.

In the year after the policy was implemented, school-related arrests for felonies fell alongside those for misdemeanor crimes, as the district and its law enforcement partners lowered arrests simply by not making them – across the board. And after signing the agreement, Sheriff Israel instructed deputies to issue lawbreaking juveniles tickets in lieu of arrests. In fact, Israel made the issuance of civil citations mandatory for deputies and school resource officers even for second- and third-time misdemeanor offenders.

In October 2016, during the re-signing ceremony with the district, Israel boasted, “We have drastically cut down on juvenile arrests” in order to “blow up” the school-to-prison pipeline. He said his office is giving law-breaking youth “second, third chances.”

“Sheriff Israel can boast that arrests are down in Broward County [but] that tends to happen when you stop arresting,” Eden said. “That does not mean that schools are safer.”

Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

Also, as RealClearInvestigations recently reported, the Broward district quietly funneled thousands of violent felons back into the classroom rather than allowing incarcerated juveniles to continue to study in jail, where teachers are also assigned to instruct them. Under its so-called “re-engagement” program, when convicted felons committed further felonies while in the Behavior Intervention Program, they were not arrested but rather given a time-out — and then reassigned back to regular schools.

The PROMISE and Behavior Intervention Programs have not accomplished the core objectives they were created to achieve in 2013 – closing the racial disparity in suspensions, expulsions and arrests between black students and white students. That gap is now wider than ever, in spite of a “very aggressive” Broward system goal of decreasing the black arrest rate by 5 percent each year and 33 percent overall.

Last year, blacks were suspended at 3.4 times the rate of whites, according to internal school district reports, up from 2.3 times before the race-based discipline reforms.

Instead of rethinking the program, the district is doubling down on it.

To get numbers for suspensions and arrests for black students down further, it is putting teachers and administrators through training to examine their “whiteness” and to purify themselves of “implicit biases” that could prejudice their reaction to minority misbehavior, while encouraging empathy for factors that contribute to their misbehavior, such as “adverse childhood experiences.”

In other words, instead of blaming these students for committing a higher rate of infractions, Runcie and his team are putting teachers and principals on the spot for harboring deep-seated prejudices that lead them to “subconsciously" mete out harsher punishments for them.

Internal documents reveal that the district has already put teachers through a highly controversial two-day anti-racism training program taught by the San Francisco based Pacific Educational Group. Its training cautions white teachers against looking at black misbehavior through the lens of “whiteness” without understanding the black culture, which it claims is “loud” and “emotional."

PEG also instructs BCPS educators to self-examine, through “courageous conversations” the "privilege of being white or the right to be white,” before referring unruly students of color for punishment.

Broward officials declined to talk about the PEG training program or reveal details, including the cost of its contract with PEG. Other districts have paid PEG hundreds of thousands of dollars for the training.

At the same time, the Broward school district is attempting to put local police officers through similar anti-bias training. But it is meeting stiff resistance from at least one large agency.

School official David Watkins, who heads the district’s Office of Equity and Academic Attainment, complained that the Fort Lauderdale Police Department recently “backed out” of a controversialsurvey the district ordered to measure “implicit bias” that police and educators may harbor toward black juveniles.

A Fort Lauderdale Police Department spokeswoman confirmed that “our department is not participating” in the project, which does not guarantee the confidentiality of survey respondents and intends to share the results with civil-rights activists and the media.

Runcie has called criticism of his discipline reforms “politics,” and says it's led by conservatives who would rather talk about his ties to the Obama administration than gun control, which he says is the real issue behind the school shooting. “It’s a diversion from issues like ‘common-sense’ gun reform,” he insisted.

Runcie landed the top district job on the recommendation of Obama’s education secretary, Arne Duncan, who served as Runcie’s boss in the Chicago school system and who later hired his brother, James Runcie, in Washington.

Runcie landed the top district job on the recommendation of Obama’s education secretary, Arne Duncan, who served as Runcie’s boss in the Chicago school system and who later hired his brother, James Runcie, in Washington.

Robert Runcie said he has no plans to make changes in the program other than to “enhance” police presence on campuses to respond faster to potential school shootings.

“We’re not going to dismantle a program that’s been successful in the district because of false information that’s been out there,” said Runcie.

“We’re not going to dismantle a program that’s been successful in the district because of false information that’s been out there,” said Runcie.

No comments:

Post a Comment