Chronicle exclusive: Bay Area death toll from drug overdoses passes 10,000

More than 10,000 people have died across the Bay Area in the drug overdose epidemic, but the main killer hasn’t been prescription painkillers for several years — methamphetamine is now the biggest cause of deaths, and overdoses on the superpotent opioid fentanyl are spiking.

Nationally, hundreds of thousands of people have died in the opioid overdose crisis, using prescription painkillers and similar street drugs like heroin and fentanyl.

The Bay Area was never as hard hit as other parts of the country by prescription opioid overdoses. But it has endured an epidemic of deaths from a variety of other street drugs that is continuing to evolve and concern public health officials.

- A Chronicle analysis of data from the California Department of Public Health found that 10,005 people have died in the nine Bay Area counties since the state began tracking overdose deaths in 2006, though that is almost certainly fewer than the number of actual drug deaths.

The methamphetamine crisis is a new-old problem, public health officials said. Meth was widespread in the 1990s and never really went away, but the number of people now dying from it — and from dangerous combinations of methamphetamine and potent opioids like fentanyl — is new, and alarming.

“It’s the new speedball,” said 58-year-old Stevon Williams, a homeless Air Force veteran in San Francisco, describing the “goofball,” which is replacing the old injection combination of cocaine and heroin. “That combo of meth and fentanyl does the same thing. A lot of people like that.” Though the public health data demonstrate shifting drug-use trends across the state, it is less precise at capturing overdose deaths caused by multiple drugs. Indeed, the state data as a whole are more subjective than most public health experts would like. It’s dependent upon how coroners and others label the cause of death, and some deaths are investigated much more thoroughly than others.

“It’s important when we’re thinking about overdose deaths that what we’re looking at isn’t necessarily the truth with a capital T,” said Dr. Matt Willis, public health officer for Marin County. “There’s a lot of bias built into the reporting.”

But the data back up what health care providers, addiction experts and users themselves are experiencing firsthand: Drug overdoses, even in communities spared from the worst of the opioid epidemic, are a public health crisis.

Geographic variations: The data were obtained from the California Opioid Overdose Surveillance Dashboard, and the Chronicle analysis is a unique examination of the drug overdose epidemic in the Bay Area as a region.

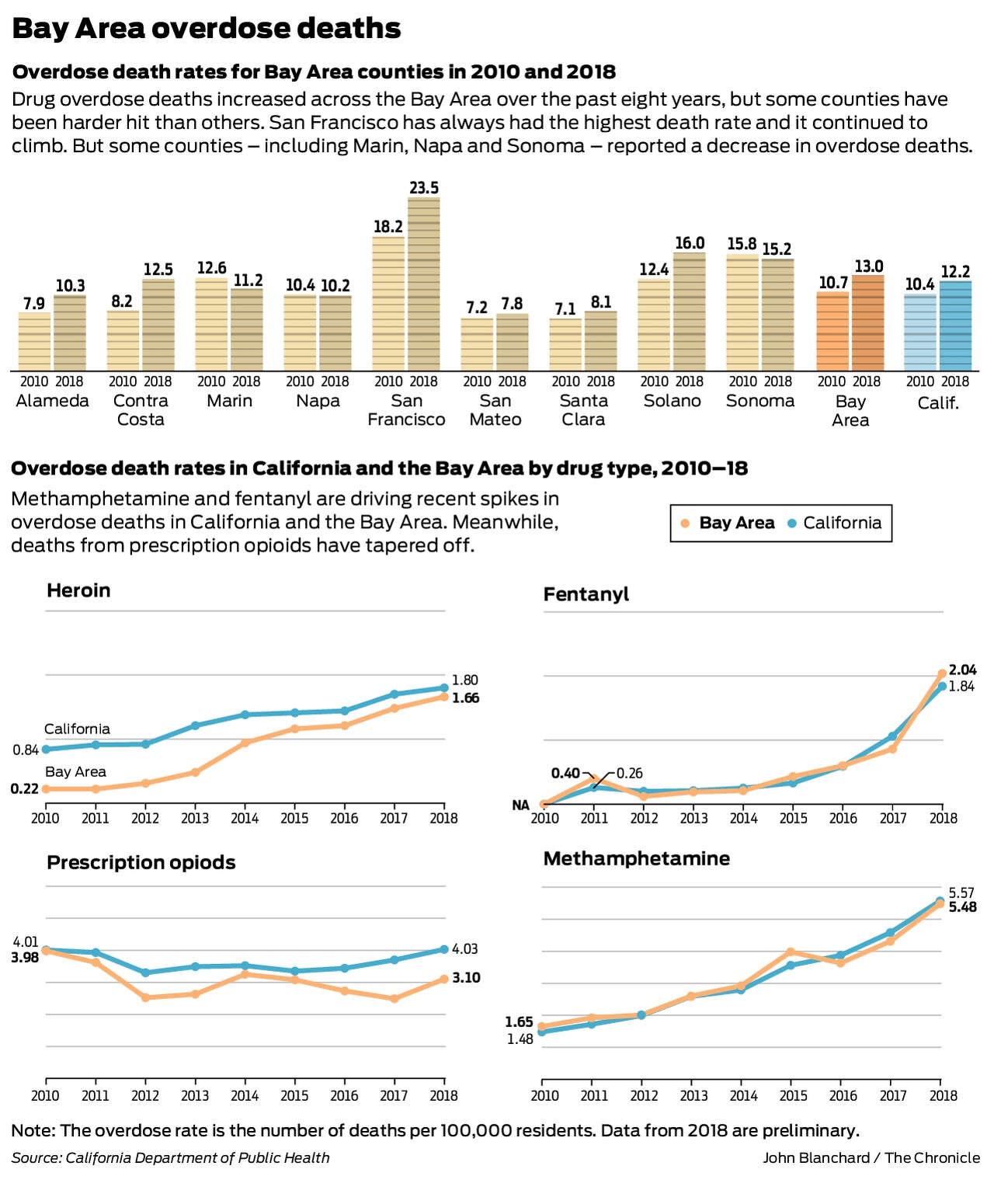

The Bay Area consistently has had somewhat lower rates of prescription opioid overdose deaths than the rest of the state, especially compared with some rural counties in Northern California where rates were 10 or 20 times higher. But for all drug overdoses, the Bay Area as a whole comes in close to the state average, about 10 to 12 deaths per 100,000 people per year.

Some local counties are notably higher than others. San Francisco has the highest rates of drug overdose deaths — about 23 per 100,000 in 2018. The North Bay counties of Sonoma and Solano also have higher death rates than the Bay Area average, about 15 per 100,000.

Santa Clara and San Mateo have the lowest rates, around 8 deaths per 100,000 last year.

“There are marked differences in relatively small geographic areas. I couldn’t tell you why,” said Dr. Scott Morrow, public health officer for San Mateo County.

Drug overdose deaths have been up and down during the past decade in the Bay Area, but they reached a decade high of 13 deaths per 100,000 residents in 2018, according to preliminary state data.

The overall death toll doesn’t tell the whole story, though.

Prescription overdose death rates have fallen slightly in the Bay Area, but deaths from heroin have been steadily increasing. And deaths from fentanyl — a synthetic opioid about 50 times more potent than heroin — have exploded in the past four years.

Opioids as a whole are still bigger killers than methamphetamine alone. But meth stands apart as the single largest killer. And that has public health officials concerned — and confused.

“Meth is not usually a very deadly drug,” said Dr. Daniel Ciccarone, a national drug use and policy expert at UCSF.

Opioids, and especially fentanyl, are so deadly because they can quickly shut down the respiratory system. Methamphetamine kills by essentially overstimulating the heart or the brain, leading to a heart attack or stroke. But in the past, only people who already had cardiovascular issues were at risk of overdoing it with meth — now, younger, otherwise healthy people are dying too.

The rise in meth overdose deaths raises questions, Ciccarone said. Are more people using meth? Is the drug itself different and more potent? Does combining meth with fentanyl make it deadlier?

Ciccarone said investigations of the drug supply have found that the meth sold in the United States is indeed stronger than what people were using 10 or 20 years ago, when meth was primarily made in backyard labs. It’s now manufactured by global drug cartels.

“We have a drug coming in that’s at 90% purity and much higher potency. But we need more studies to say if the meth is more deadly,” Ciccarone said.

Deadly combinations: Combining drugs, especially meth with an opioid like fentanyl, is especially concerning to public health officials. It’s difficult to track those deaths, and dual addictions are more complicated to treat.

Purposely taking methamphetamine with fentanyl, one hit after the other, is like juggling dynamite — but hard-core addicts say they need it. The high of the methamphetamine sometimes needs counteracting with the chill-out effect of the fentanyl, they say. Or the deeply sedated state caused by fentanyl has to be offset by the rush of meth.

“Speed a lot of times gets you geeked out, with your heart racing and your head pounding, and then fentanyl evens you out,” said Shauna Arteago, 45, who has been homeless but now lives in a San Francisco single-room apartment. “I smoke them one at a time, and you’ve got to be careful, because fentanyl can kill you. I’ve overdosed three times, the last time a few months ago.”

Those who work daily with addicts on the street don’t need statistics to tell them the overdose problem is growing — particularly among the homeless.

Capt. Carl Fabbri, commander of the Tenderloin Police Station, said he often feels like he’s shoveling sand into tides when he and his officers try to intervene with addicts on the street, and it’s heartbreaking.

“We’ve made progress on the dealers, but the victims — the users? It’s almost out of our hands, there are so many,” he said. “It is terribly sad.”

A 39-year-old homeless longtime addict who goes by the street name of Country fired up a bubble — pipe load — of meth near the Ferry Building and said overdoses and addictions in the street “have gotten off the hook in the last year or so.”

“It’s so much more than ever, and I’ve seen it all,” he said.

“It makes me sad seeing so many people do so much drugs out here, but we’re stuck. We need help. You think we all want to be addicted to this crap? No way.”

San Francisco public health officials, who have been collecting data on overdose deaths involving more than one drug, say their analyses show that overdose rates with both meth and fentanyl have more than doubled in just the past two years.

A decade ago, meth was causing only a dozen or so deaths a year and fentanyl wasn’t even tracked. In 2018, roughly 50 people died with both drugs in their system — dozens more died from one or the other.

“The reality is that most drug use is poly drug use. It’s not unusual for people to be using more than one drug,” said Dr. Phillip Coffin, director of substance use research for the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

Combining meth and fentanyl may be especially risky for a lot of reasons, among them that meth, in particular, leads to “chaotic behaviors” that may prevent people from practicing safer drug practices, he said.

For example, harm-reduction experts advise than anyone using fentanyl start with a small dose and that they never get high alone, so that if they overdose, someone can treat them with Narcan. But if they’re using meth too, people may not be thinking clearly enough to take those precautions.

The “goofball” is not just a San Francisco problem. What’s not clear from data and anecdotal information is how often people are choosing to combine meth with an opioid verus being “poisoned” by fentanyl that is sometimes added to other drugs without users knowing it, public health officials say.

Fentanyl isn’t necessarily pervasive in all Bay Area counties just yet — or it’s not being identified as a cause of death. But not all counties have the laboratory resources to test for the specific opioid found in a person after death. When fentanyl is identified in an overdose, it’s often impossible to know whether the person chose to use it or took it by accident.

“The combination of opioids and stimulants is common,” said Dr. Ori Tzvieli, deputy health officer with Contra Costa County. “But did they die because they were a meth addict and they ended up buying some with fentanyl in it? Or did they die because they’re someone with an opioid overuse disorder who’s using fentanyl now?”

Erin Allday and Kevin Fagan are San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. Email: eallday@sfchronicle.com, kfagan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @erinallday, @KevinChron

CONTACT: onlineghosthacker247 @gmail. com

ReplyDelete-Find Out If Your Husband/Wife or Boyfriend/Girlfriend Is Cheating On You

-Let them Help You Hack Any Website Or Database

-Hack Into Any University Portal; To Change Your Grades Or Upgrade Any Personal Information/Examination Questions

-Hack Email; Mobile Phones; Whatsapp; Text Messages; Call Logs; Facebook And Other Social Media Accounts

-And All Related Services

- let them help you in recovery any lost fund scam from you

onlineghosthacker Will Get The Job Done For You

onlineghosthacker247 @gmail. com

TESTED AND TRUSTED!!!